The Quiet Bravery of Rosa Parks, December 1, 1955

Seventy years ago today Rosa Parks was arrested for refusing to give up her seat on a city bus in Montgomery, Alabama. But why did this happen? Why did Mrs. Parks decide to stay in that seat? There are two simple explanations commonly believed by many people: either (1) Mrs. Parks was so tired on her way home from her work that day and so tired of years of the indignities of Jim Crow segregation that she was just fed up, or (2) it was a setup, a protest planned in advance by Mrs. Parks and the NAACP to challenge Jim Crow laws in court. Neither of these is completely true, and neither is completely false. The underlying history is a bit more complex.

In the 1940s Rosa Parks joined the NAACP, in which her husband Raymond had long been active, and she became secretary and youth director of the Montgomery chapter. She worked to help Black citizens in their often thwarted efforts to register to vote. In 1944 she initiated the founding of the Committee for Equal Justice for the Rights of Mrs. Recy Taylor, who had been brutality gang raped, and beyond that case she continued to work on behalf of other women. In 1949 she organized members of the NAACP youth group to mount a protest against segregation in the Montgomery Public Library system. Thus, Rosa Parks was politically astute, experienced, and informed on matters of race, segregation, and the law.

She also had personal experience of the petty cruelties of bus drivers. In November 1943 she decided to go downtown to try a second time to register to vote. She got on the bus, paid her fare, and started down the aisle to find a place to stand towards the back, though the back of the bus was already full. The driver, James F. Blake, told her to get off and enter by the rear door, as some drivers insisted of Black passengers. But the rear door stepwell was crowded with standing riders, and she objected. The driver tugged on her sleeve and told her, “Get off my bus!” Mrs. Parks dropped her purse, and as she bent to pick it up she sat ever so briefly on one of the empty “white” seats, a subtly defiant act that surely angered Blake even more. She got off and vowed never again to get on a bus with that driver.

Twelve years later, on Thursday, December 1, 1955, Mrs. Parks got on the Cleveland Avenue bus as usual after work. Whatever was on her mind that evening, she did not notice the driver, but took a seat in the row right behind the seats reserved for white passengers. As the reserved “white” seats then became filled, the driver told the four Black passengers in the next row back to get up so that a white rider could sit there. No Black person could sit in the same row as a white person, even across the aisle. Three of the passengers got up, but Mrs. Parks decided that the time had come, and on recognizing Blake as the driver, she may have become even more determined. She had not planned to be arrested that day, but she knew exactly what to do and how to respond when it happened.

Very few of us, I suspect, could have matched her quiet confidence and equanimity. But as much as her response reflected her personality and quiet demeanor, even that was prepared. The previous summer Mrs. Parks had accepted a scholarship to attend a two-week workshop on activism, voter registration, and school desegregation directed by Septima Clark at the interracial Highlander Folk School in Tennessee. The experience and training she gained there not only increased her resolve, it undoubtedly helped her to remain calm, composed, and, above all, brave, when she was confronted by Blake, for every Black passenger on that bus would have known instantly that the situation was extremely volatile.

Blake asked Mrs. Parks, “Are you going to stand up?” “No,” she answered. “Well,” he said, “I am going to have you arrested.” She replied quietly, “You may do that.” Blake called his supervisor, and two city police officers soon arrived and arrested Mrs. Parks under Chapter 6, Section 11, of the Montgomery City Code. According to the officers’ arrest report, they charged her with “refusing to obey order of bus driver.” She was taken to city hall, booked, and transferred to the city jail.

The news spread rapidly, and when she heard what had happened, Jo Ann Robinson, a faculty member at Alabama State College, went into action. With the help of another faculty member and two students, Robinson worked the college mimeograph machines through the night to produce 52,500 copies of a notice she had written:

“Another Negro woman has been arrested and thrown in jail because she refused to get up out of her seat on the bus for a white person to sit down. It is the second time since the Claudette Colvin case that a Negro woman has been arrested for the same thing. This has to be stopped. Negroes have rights, too, for if Negroes did not ride the buses, they could not operate. Three-fourths of the riders are Negroes, yet we are arrested, or have to stand over empty seats. If we do not do something to stop these arrests, they will continue. The next time it may be you, or your daughter, or mother. This woman’s case will come up on Monday. We are, therefore, asking every Negro to stay off the buses Monday in protest of the arrest and trial. Don’t ride the buses to work, to town, to school, or anywhere on Monday. You can afford to stay out of school for one day if you have no other way to go except by bus. You can also afford to stay out of town for one day. If you work, take a cab, or walk. But please, children and grown-ups, don’t ride the bus at all on Monday. Please stay off of all buses Monday.”

On Monday, Rosa Parks was convicted, and the Montgomery Bus Boycott began. It lasted not just that Monday; it continued for 381 days, bringing much needed social, cultural, and legal change to the American landscape.

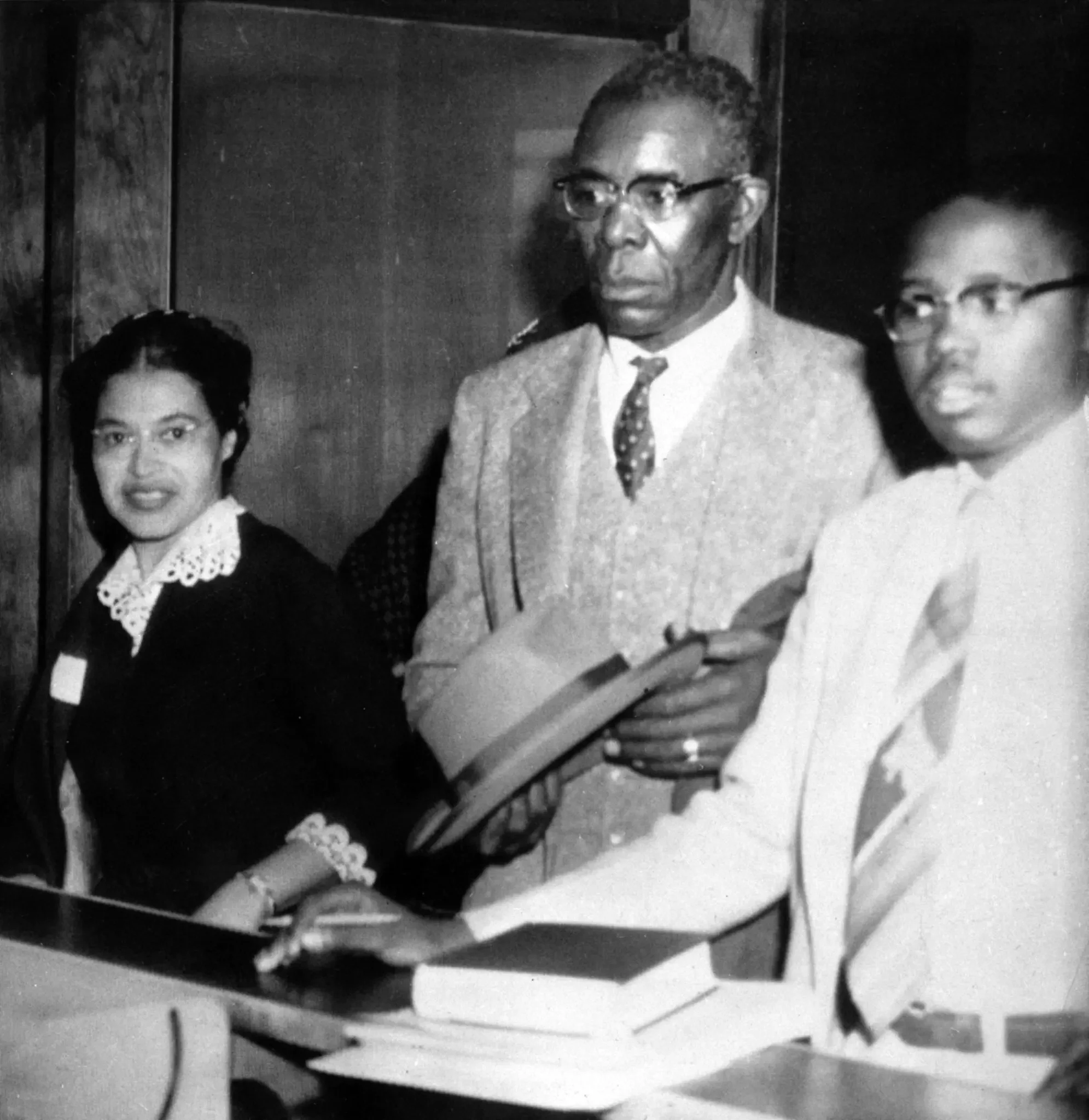

Rosa Parks, E.D. Nixon, and Fred Gray signing her appeal bond, Dec. 5, 1955